By Video Editor

Whether in crowded urban streets or in villages, a common sight throughout the 20th century was that of Chinese children in groups, reading palm-sized picture books. Each picture came with a description advancing the plot, usually adapted from a famous classical novel like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms or Outlaws of the Marsh. The immersive combination of gripping stories with vivid and dynamic illustration, known as lianhuanhua or “linked pictures,” was a well-loved staple amog Chinese youth.

Though mostly a product of modern printing and mass literacy, the origins of lianhuanhua can be traced back to ancient China. Stone engravings used in memorial services during the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) and Dunhuang murals of the Northern Wei dynasty (386 – 534) used linked pictures to depict the stories or biographies of certain people. On lacquered coffins at Mawangdui near Changsha in Hunan province, containing the tombs of three people from the Western Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD), are serial pictures that illustrate stories about “a man devouring a snake” and “the goat that rode a crane in flight.” Most of the Dunhuang murals recount stories about the previous incarnations of the Buddha, when he experienced life as both humans and animals. Murals at the Mogao Caves drawn in the Northern Wei Dynasty depict Buddhist stories such as the “Deer of Nine Hues” or “King Shipi Offers His Flesh to Save a Pigeon.” Handscroll paintings in the Six Dynasties period (AD 222 – 589) also display features of serial pictures. These include paintings by Gu Kaizhi (344 – 406), “Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies” and “Nymph of the Luo River.” The repeated presence of figures on the handscrolls to illustrate the plot and simple captions placed beside the paintings are similar to the format found in lianhuanhua.

The spread of Buddhism during the Sui (581 – 618) and Tang (618 – 907) dynasties was aided by the appearance of silk streamers decorated with paintings and captions promoting the religion. They would often be placed upright at the sites where Buddhist monks practiced cultivation or conducted rituals. This was accompanied by a popular literary style called bianwen, or transformation texts, that grew out of the Buddhist teachings. Oral stories were written down and each paragraph illustrated using a painting of a Buddhist story or legend.

Proto-lianhuanhua was greatly aided by the introduction of advanced printing techniques in the Song Dynasty (960 – 1279). Woodblock printing, a method of printing on cloth and paper that was invented in the Sui and Tang dynasties and reached its maturity in the Song dynasty, made it easier to print pictures and add captions to them. The re-publication of the Biographies of Exemplary Women in 1063, originally compiled by Han Dynasty scholar Liu Xing, was the earliest book with linked pictures, and can be considered the earliest lianhuanhua.

Linked pictures were commonly used in the publication of novels and plays in the Ming (1368 –1644) and Qing (1644 – 1912) dynasties. Some of them featured dozens or even over one-hundred illustrations at the beginning of the text. These popular media laid the foundations for modern lianhuanhua.

Before the end of the Qing Dynasty, most literature was produced using woodblock printing. Words and pictures were carved out on wood to make a printing plate, and ink was then spread across the block to print the text. Ceramic movable type, the earliest movable type known, was invented during the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127). Movable type printing is a system of printing that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual letters or punctuation) by making up single tablets in lines. The tablets can be separated after use and rearranged for another printing. Moveable type was costly and was limited to specialized use. But in the 19th century, lithographic printing introduced to China from the West surmounted many of these difficulties. Lithography used images drawn in wax or other oily substances applied to stone as a medium to transfer ink to the sheet. This facilitated the creation and dissemination of popular media, including lianhuanhua.

In 1884, China’s first modern newspaper, the Shen Bao or Shanghai News, published its Dianshizhai Pictorial (點石齋畫報), a supplement that focused on political reporting. Owing to the limited availability of photography, the pictorials recorded current events, street scenes, traditional activities, and advances in industrial machinery. Between 1884 and 1898, Dianshizhai Pictorial published over 4,000 illustrations.

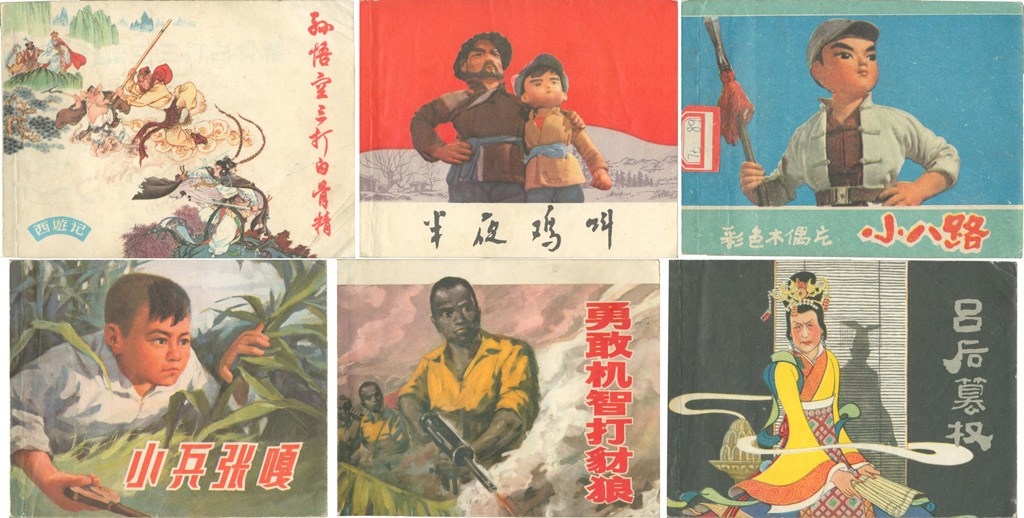

In 1899, the Wenyi Book Company in Shanghai published its lithograph, Complete Illustrations of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. It was the first pictorial book to depict a fully literary classic. Lianhuanhua came into its own in the 1920s and 1930s. The Shanghai World Book Company, which between 1925 and 1929 published adaptations of classic works like the Journey to the West, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Outlaws of the Marsh, Investiture of the Gods, and the Story of Yue Fei, coined the term “lianhuan tuhua.” By the 1950s, the term was condensed to “lianhuanhua.” Besides classical novels and legends, lianhuanhua also depicted works of theater and opera, with the background illustrations inspired by the stage sets. The most famous works among them were Mr. Wang by Ye Qianyu, and Zhang Leping’s Wanderings of Sanmao.

Lianhuanhua helped promote historical epics and the moral values of benevolence, justice, loyalty, and honesty. It was credited with popularizing and passing down traditional culture. After 1949, when the communists seized power in China, lianhuanhua became a powerful instrument of propaganda that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) used to promote destructive and deadly political campaigns like the Land Reform campaign and the Great Leap Forward. It was also used during the Korean War to demonize the United States.

The 1950s and 1960s marked the last great boom of lianhuanhua. Most prestigious in the field were artists Shen Manyun, Zhao Hongben, Qian Xiaodai, and Chen Guangyi, “the four great cartoonists.” While Zhao Sandao, Bi Ruhua, Yan Meihua, and Xu Hongda were known as, “the four lesser cartoonists.” A common industry saying, “Gu in the south, Liu in the north,” referred to lianhuanhua artists Gu Bingxin from Shanghai and Liu Jiyou of Tianjin.

Though often stained by the demands of communist propaganda, the lianhuanhua works centered around traditional themes, like Zhao Hongben’s and Qian Xiaodai’s depiction of “Monkey King Thrice Defeats the White Bone Demon,” and Wang Shuhui’s rendition of the Yuan Dynasty romance, The Story of the Western Wing. In 1957, the Shanghai People’s Art Publishing House produced the longest of the lianhuanhua — a 60-volume adaptation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms (the original novel contained 120 chapters) featuring over 7,000 illustrations.

The Cultural Revolution (1966 – 1976) all but devastated the art of lianhuanhua, which was completely subordinated to the communist fanaticism of the movement. Making a complete break with the literary classics and traditional tales, “Cultural Revolution lianhuanhua” instead adapted the contents of the revolutionary Eight Model Operas approved by Jiang Qing, the domineering wife of communist leader Mao Zedong.

Following the death of Mao and the end of the Cultural Revolution, the popularization of TV dramas and other forms of communication supplanted traditional media. Lianhuanhua in particular, having sunk to its lowest point during the Cultural Revolution, was unable to make a comeback as China imported Western and Japanese cartoons and comics. Today, lianhuanhua is something of a rarity, and is seen mostly in museums.

Lianhuanhua artists excelled at fusing a variety of techniques into their creations, giving their art great diversity and expressive potential. Most lianhuanhua were rendered in line drawings, sketches, and paintings.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, popular novels often included portraits of the main characters at the beginning of the novels and sometimes at the start of each chapter. Learning from traditional fine-lined pen portraits, lianhuanhua used line drawing technique to portray figures, scenes and objects. This was the most common form of lianhuanhua. Writing brushes were employed in line drawing of early lianhuanhua, such as those rendering, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, “Pangu Separates Heaven and Earth,” and “Legends of the Heroes on Mount Liang.”

Other lianhuanhua were composed using fine brushwork. Representative works include the Story of the Western Wing by Wang Shuhui, as well as “Wu Song Fights the Tiger,” and “The Monkey King,” by Liu Jiyou.

Cancel anytime

Using our website

You may use the The Middle Land website subject to the Terms and Conditions set out on this page. Visit this page regularly to check the latest Terms and Conditions. Access and use of this site constitutes your acceptance of the Terms and Conditions in-force at the time of use.

Intellectual property

Names, images and logos displayed on this site that identify The Middle Land are the intellectual property of New San Cai Inc. Copying any of this material is not permitted without prior written approval from the owner of the relevant intellectual property rights.

Requests for such approval should be directed to the competition committee.

Please provide details of your intended use of the relevant material and include your contact details including name, address, telephone number, fax number and email.

Linking policy

You do not have to ask permission to link directly to pages hosted on this website. However, we do not permit our pages to be loaded directly into frames on your website. Our pages must load into the user’s entire window.

The Middle Land is not responsible for the contents or reliability of any site to which it is hyperlinked and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Linking to or from this site should not be taken as endorsement of any kind. We cannot guarantee that these links will work all the time and have no control over the availability of the linked pages.

Submissions

All information, data, text, graphics or any other materials whatsoever uploaded or transmitted by you is your sole responsibility. This means that you are entirely responsible for all content you upload, post, email or otherwise transmit to the The Middle Land website.

Virus protection

We make every effort to check and test material at all stages of production. It is always recommended to run an anti-virus program on all material downloaded from the Internet. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss, disruption or damage to your data or computer system, which may occur while using material derived from this website.

Disclaimer

The website is provided ‘as is’, without any representation or endorsement made, and without warranty of any kind whether express or implied.

Your use of any information or materials on this website is entirely at your own risk, for which we shall not be liable. It is your responsibility to ensure any products, services or information available through this website meet your specific requirements.

We do not warrant the operation of this site will be uninterrupted or error free, that defects will be corrected, or that this site or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or represent the full functionality, accuracy and reliability of the materials. In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including, without limitation, loss of profits, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damages whatsoever arising from the use, or loss of data, arising out of – or in connection with – the use of this website.

Last Updated: September 11, 2024

New San Cai Inc. (hereinafter “The Middle Land,” “we,” “us,” or “our”) owns and operates www.themiddleland.com, its affiliated websites and applications (our “Sites”), and provides related products, services, newsletters, and other offerings (together with the Sites, our “Services”) to art lovers and visitors around the world.

This Privacy Policy (the “Policy”) is intended to provide you with information on how we collect, use, and share your personal data. We process personal data from visitors of our Sites, users of our Services, readers or bloggers (collectively, “you” or “your”). Personal data is any information about you. This Policy also describes your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your personal information.

If after reading this Policy you have additional questions or would like further information, please email at middleland@protonmail.com.

PERSONAL DATA WE COLLECT AND HOW WE USE IT

We collect and process personal data only for lawful reasons, such as our legitimate business interests, your consent, or to fulfill our legal or contractual obligations.

Information You Provide to Us

Most of the information Join Talents collects is provided by you voluntarily while using our Services. We do not request highly sensitive data, such as health or medical information, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, etc. and we ask that you refrain from sending us any such information.

Here are the types of personal data that you voluntarily provide to us:

As a registered users or customers, you may ask us to review or retrieve emails sent to your business. We will access these emails to provide these services for you.

We use the personal data you provide to us for the following business purposes:

Information Obtained from Third-Party Sources

We collect and publish biographical and other information about users, which we use to promote the articles and our bloggers who use our sites. If you provide personal information about others, or if others give us your information, we will only use that information for the specific reason for which it was provided.

Information We Collect by Automated Means

Log Files

The site uses your IP address to help diagnose server problems, and to administer our website. We use your IP addresses to analyze trends and gather broad demographic information for aggregate use.

Every time you access our Site, some data is temporarily stored and processed in a log file, such as your IP addresses, the browser types, the operating systems, the recalled page, or the date and time of the recall. This data is only evaluated for statistical purposes, such as to help us diagnose problems with our servers, to administer our sites, or to improve our Services.

Do Not Track

Your browser or device may include “Do Not Track” functionality. Our information collection and disclosure practices, and the choices that we provide to customers, will continue to operate as described in this Privacy Policy, whether or not a “Do Not Track” signal is received.

HOW WE SHARE YOUR INFORMATION

We may share your personal data with third parties only in the ways that are described in this Privacy Policy. We do not sell, rent, or lease your personal data to third parties, and We does not transfer your personal data to third parties for their direct marketing purposes.

We may share your personal data with third parties as follows:

There may be other instances where we share your personal data with third parties based on your consent.

HOW WE STORE AND SECURE YOUR INFORMATION

We retain your information for as long as your account is active or as needed to provide you Services. If you wish to cancel your account, please contact us middleland@protonmail.com. We will retain and use your personal data as necessary to comply with legal obligations, resolve disputes, and enforce our agreements.

All you and our data are stored in the server in the United States, we do not sales or transfer your personal data to the third party. All information you provide is stored on a secure server, and we generally accepted industry standards to protect the personal data we process both during transmission and once received.

YOUR RIGHTS/OPT OUT

You may correct, update, amend, delete/remove, or deactivate your account and personal data by making the change on your Blog on www.themiddleland.com or by emailing middleland@protonmail.com. We will respond to your request within a reasonable timeframe.

You may choose to stop receiving Join Talents newsletters or marketing emails at any time by following the unsubscribe instructions included in those communications, or you can email us at middleland@protonmail.com

LINKS TO OTHER WEBSITES

The Middle Land include links to other websites whose privacy practices may differ from that of ours. If you submit personal data to any of those sites, your information is governed by their privacy statements. We encourage you to carefully read the Privacy Policy of any website you visit.

NOTE TO PARENTS OR GUARDIANS

Our Services are not intended for use by children, and we do not knowingly or intentionally solicit data from or market to children under the age of 18. We reserve the right to delete the child’s information and the child’s registration on the Sites.

PRIVACY POLICY CHANGES

We may update this Privacy Policy to reflect changes to our personal data processing practices. If any material changes are made, we will notify you on the Sites prior to the change becoming effective. You are encouraged to periodically review this Policy.

HOW TO CONTACT US

If you have any questions about our Privacy Policy, please email middleland@protonmail.com

The Michelin brothers created the guide, which included information like maps, car mechanics listings, hotels and petrol stations across France to spur demand.

The guide began to award stars to fine dining restaurants in 1926.

At first, they offered just one star, the concept was expanded in 1931 to include one, two and three stars. One star establishments represent a “very good restaurant in its category”. Two honour “excellent cooking, worth a detour” and three reward “exceptional cuisine, worth a

Thank you for your participation,

please Log in or Sign up to Vote

123Sign in to your account