By Zhang Yi

The history of ice cream can be traced back to the Chinese some 3,000 years ago, a time when the emperors were some of the fortunate royalties and high rank families who could enjoy such a treat. Of course, the ancient form of ice cream was different from what it is today, but it has evolved over time through different recipes.

In the olddays, huge ice blocks, formed in winter, were heavily sought after and stowed away. In particular, the Chinese imperial palace would have these blocks of ice stored in the basement ready for use with the arrival of summer’s heat.

It is commonly known that potassium nitrate (saltpeter) has been used as a major ingredient in producing gunpowder since ancient times. It was also found, however, that saltpeter, when melted in water, could absorb such a great amount of heat as to freeze the water. Accordingly, ice had already been produced in China in the Tang Dynasty (618–907).

Duyang Zabian, a collection of Tang Dynasty stories by Su E, recorded: “In scorching summer, put a handful of saltpeter into a wok of water and boil it. Put the boiled water in a bottle and have it sealed. Then re-boil the water and hurriedly throw it into a stream. This way, ice is created in the stream, known as ‘ice blocks for a feast.’”

There is a note on “Pearls of Ice” in Xu Yijian Zhi, a supernatural fiction infused with historical sources and miscellaneous notes, written by Yuan Haowen (1190–1257), who was born during the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234): “Tao River outside Lintao City was frozen solid in winter months, producing ice lumps that resembled Euryale Ferox (*) seeds, as pure as round-shaped earlobes. Rich families in Tao Town harvested round-shaped ice lumps and stored them in icehouses for summer use. In scorching summer, tea was flavored with honey and cooled with round-shaped ice, which looked like pearls of ice.”

Although the availability of ice year-round existed in the Tang Dynasty, it wasn’t until the Song Dynasty (960–1279) that iced beverages gained popularity. The blending of exotic ingredients with ice gave rise to a whole new trend in iced drinks. Beverage stores began offering a wide variety of iced drinks, including “honey water with ice pearls” and “”lychee ice cream.” Another popular dessert was ice cheese, made of juice, milk, and ice cubes.

Yang Wanli (1127–1206), one of the “four masters” of Song Dynasty poetry, described vendors selling ice desserts along the streets:

AT HIGH NOON IN JUNE,

IN THE STEAMING IMPERIAL CAPITAL

RESIDENTS DRIP WITH SWEAT VOICES OF VENDORS SELLING ICE ACROSS THE RIVER ARE

A JOY FOR PASSERS-BY,

EVEN WITHOUT A TASTE OF ICE.

Ice stores in Bianjing (now Kaifeng), the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty, sold ice pearls in crystal sugar. Iced sweet-sour plum juice was another flavorful drink at the time. Ice stores in Lin’an (now Hangzhou), the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty, sold “iced bean soup” and “iced plum blossom wine.” Some celebrated painters of the Song Dynasty, like Liu Songnian (1174–1224), even painted in their works scenes of cold drinks being sold.

In the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) iced drinks experienced another breakthrough. In the book, Principles of Correct Diet, a monograph on medicated diet, by Hu Sihui, a royal doctor during the time of the Yuan Dynasty, the procedure to make suyou (butter), tihu (the finest cream), and baisuyou (white butter) is described: “Take congealed milk and have it boiled dry to make suyou. Take the best-quality suyou, and have it boiled dry, filtered, and stored in a big jar. The unfrozen part in the center of the jar is called tihu. Put fresh milk in a jar to have it sour with fermentation, and then use a pestle to churn the fermented milk for thousands of times so as to separate the paste from the remaining liquid. The resulting paste is called baisuyou.”

Zhu Yizun (1629–1709), an author and poet during the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), recorded cheese-making procedures in his book, The Grand Secrets of Diets: “From milk comes junket; from junket comes crust pastry; from raw crust pastry comes ripe crust pastry; from ripe crust pastry comes tihu. Add a half cup of water and three pinches of flour into a bowl of milk, stew it until it boils, and add icing sugar to it. Then cook it by a quick fire, churning it for a while with a ladle. When it is well-cooked, have it filtered and poured into a bowl, which tastes best with sugar and ground dried mint.”

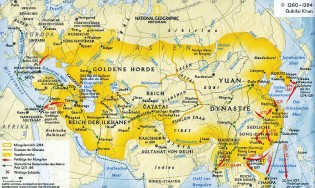

When Marco Polo, an Italian merchant traveler, came to China, he was heartily welcomed and offered ice cheese by Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan Dynasty.

According to accounts of The Travels of Marco Polo, there indeed existed ice cheese during the Yuan Dynasty. Chen Ji, an imperial preceptor of the Yuan Dynasty, described the royal treat of ice cheese in his poem:

“Snowy ice cheese on a golden plate

Awarded as top honor, at the imperial court.”

In 1295, Kublai Khan revealed the technique of making ice cheese to Marco Polo, who brought it back to Italy. Instead of following the recipe exactly, Marco Polo altered it by adding yak’s milk into the ice cubes, which in turn made the ice cheese creamy. It was this slight change with the addition of milk to ice that became popular.

After being introduced to Italy, the technique of making ice cheese was kept secret until it was sold to France some 300 years later at a very high price. Ice cheese was subsequently introduced to England, where the British helped to develop it into what ice cream is today.

In 1560, due to the Italian noblewoman Catherine de’ Medici, wife of King Henry II of France, ice cream recipes experienced further changes. The Italian chefs she brought with her from Florence, Italy, invented semi-solid ice cream flavored with butter, milk, and spices.

Additionally, floral patterns were carved on the ice cream to make it more decorative. Since then, ice cream, in all sorts of flavors and styles, has become an enjoyable treat worldwide.

* Euryale Ferox is a flowering plant that produces starchy white edible seeds, which are used in traditional Chinese medicine.

Cancel anytime

Using our website

You may use the The Middle Land website subject to the Terms and Conditions set out on this page. Visit this page regularly to check the latest Terms and Conditions. Access and use of this site constitutes your acceptance of the Terms and Conditions in-force at the time of use.

Intellectual property

Names, images and logos displayed on this site that identify The Middle Land are the intellectual property of New San Cai Inc. Copying any of this material is not permitted without prior written approval from the owner of the relevant intellectual property rights.

Requests for such approval should be directed to the competition committee.

Please provide details of your intended use of the relevant material and include your contact details including name, address, telephone number, fax number and email.

Linking policy

You do not have to ask permission to link directly to pages hosted on this website. However, we do not permit our pages to be loaded directly into frames on your website. Our pages must load into the user’s entire window.

The Middle Land is not responsible for the contents or reliability of any site to which it is hyperlinked and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Linking to or from this site should not be taken as endorsement of any kind. We cannot guarantee that these links will work all the time and have no control over the availability of the linked pages.

Submissions

All information, data, text, graphics or any other materials whatsoever uploaded or transmitted by you is your sole responsibility. This means that you are entirely responsible for all content you upload, post, email or otherwise transmit to the The Middle Land website.

Virus protection

We make every effort to check and test material at all stages of production. It is always recommended to run an anti-virus program on all material downloaded from the Internet. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss, disruption or damage to your data or computer system, which may occur while using material derived from this website.

Disclaimer

The website is provided ‘as is’, without any representation or endorsement made, and without warranty of any kind whether express or implied.

Your use of any information or materials on this website is entirely at your own risk, for which we shall not be liable. It is your responsibility to ensure any products, services or information available through this website meet your specific requirements.

We do not warrant the operation of this site will be uninterrupted or error free, that defects will be corrected, or that this site or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or represent the full functionality, accuracy and reliability of the materials. In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including, without limitation, loss of profits, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damages whatsoever arising from the use, or loss of data, arising out of – or in connection with – the use of this website.

Last Updated: September 11, 2024

New San Cai Inc. (hereinafter “The Middle Land,” “we,” “us,” or “our”) owns and operates www.themiddleland.com, its affiliated websites and applications (our “Sites”), and provides related products, services, newsletters, and other offerings (together with the Sites, our “Services”) to art lovers and visitors around the world.

This Privacy Policy (the “Policy”) is intended to provide you with information on how we collect, use, and share your personal data. We process personal data from visitors of our Sites, users of our Services, readers or bloggers (collectively, “you” or “your”). Personal data is any information about you. This Policy also describes your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your personal information.

If after reading this Policy you have additional questions or would like further information, please email at middleland@protonmail.com.

PERSONAL DATA WE COLLECT AND HOW WE USE IT

We collect and process personal data only for lawful reasons, such as our legitimate business interests, your consent, or to fulfill our legal or contractual obligations.

Information You Provide to Us

Most of the information Join Talents collects is provided by you voluntarily while using our Services. We do not request highly sensitive data, such as health or medical information, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, etc. and we ask that you refrain from sending us any such information.

Here are the types of personal data that you voluntarily provide to us:

As a registered users or customers, you may ask us to review or retrieve emails sent to your business. We will access these emails to provide these services for you.

We use the personal data you provide to us for the following business purposes:

Information Obtained from Third-Party Sources

We collect and publish biographical and other information about users, which we use to promote the articles and our bloggers who use our sites. If you provide personal information about others, or if others give us your information, we will only use that information for the specific reason for which it was provided.

Information We Collect by Automated Means

Log Files

The site uses your IP address to help diagnose server problems, and to administer our website. We use your IP addresses to analyze trends and gather broad demographic information for aggregate use.

Every time you access our Site, some data is temporarily stored and processed in a log file, such as your IP addresses, the browser types, the operating systems, the recalled page, or the date and time of the recall. This data is only evaluated for statistical purposes, such as to help us diagnose problems with our servers, to administer our sites, or to improve our Services.

Do Not Track

Your browser or device may include “Do Not Track” functionality. Our information collection and disclosure practices, and the choices that we provide to customers, will continue to operate as described in this Privacy Policy, whether or not a “Do Not Track” signal is received.

HOW WE SHARE YOUR INFORMATION

We may share your personal data with third parties only in the ways that are described in this Privacy Policy. We do not sell, rent, or lease your personal data to third parties, and We does not transfer your personal data to third parties for their direct marketing purposes.

We may share your personal data with third parties as follows:

There may be other instances where we share your personal data with third parties based on your consent.

HOW WE STORE AND SECURE YOUR INFORMATION

We retain your information for as long as your account is active or as needed to provide you Services. If you wish to cancel your account, please contact us middleland@protonmail.com. We will retain and use your personal data as necessary to comply with legal obligations, resolve disputes, and enforce our agreements.

All you and our data are stored in the server in the United States, we do not sales or transfer your personal data to the third party. All information you provide is stored on a secure server, and we generally accepted industry standards to protect the personal data we process both during transmission and once received.

YOUR RIGHTS/OPT OUT

You may correct, update, amend, delete/remove, or deactivate your account and personal data by making the change on your Blog on www.themiddleland.com or by emailing middleland@protonmail.com. We will respond to your request within a reasonable timeframe.

You may choose to stop receiving Join Talents newsletters or marketing emails at any time by following the unsubscribe instructions included in those communications, or you can email us at middleland@protonmail.com

LINKS TO OTHER WEBSITES

The Middle Land include links to other websites whose privacy practices may differ from that of ours. If you submit personal data to any of those sites, your information is governed by their privacy statements. We encourage you to carefully read the Privacy Policy of any website you visit.

NOTE TO PARENTS OR GUARDIANS

Our Services are not intended for use by children, and we do not knowingly or intentionally solicit data from or market to children under the age of 18. We reserve the right to delete the child’s information and the child’s registration on the Sites.

PRIVACY POLICY CHANGES

We may update this Privacy Policy to reflect changes to our personal data processing practices. If any material changes are made, we will notify you on the Sites prior to the change becoming effective. You are encouraged to periodically review this Policy.

HOW TO CONTACT US

If you have any questions about our Privacy Policy, please email middleland@protonmail.com

The Michelin brothers created the guide, which included information like maps, car mechanics listings, hotels and petrol stations across France to spur demand.

The guide began to award stars to fine dining restaurants in 1926.

At first, they offered just one star, the concept was expanded in 1931 to include one, two and three stars. One star establishments represent a “very good restaurant in its category”. Two honour “excellent cooking, worth a detour” and three reward “exceptional cuisine, worth a

Thank you for your participation,

please Log in or Sign up to Vote

123Sign in to your account