By Staff Reporter

Those with proficient traditional Chinese arts and crafts are respected as masters. Such masters passed down not only their craftsmanship but also methods to cultivate one’s mind. Sometimes, even when a master imparted knowledge, he had to be responsible to his followers. While imparting professional knowledge, the master had to teach the students moral standards, behind which were strict regulations followed by all followers. Such regulations informed people of the dos and do nots in moral dilemmas. If a follower should cross the line, the master had the power and capacity to deprive the follower of his craftsmanship or even his or her life.

Some professions in modern China, like martial arts, dramas, paintings, traditional Chinese medicine, music, and cooking, are also marked by the tradition that masters impart professional knowledge to followers. On the other hand, in Western colleges, those who impart knowledge are called teachers, while those who acquire knowledge are called students. This way, teachers are responsible for propagating knowledge and students’ academic performance. If a student should violate a regulation, the teacher will leave him to society.

Chinese paintings feature specific brushes, ink, paper, and colors. In particular, traditional Chinese paintings follow strict theories. Despite a century of havoc, Chinese paintings still maintain their typical purity, free of any outside disturbance. Of course, certain painters and scholars have attempted to change the nature of Chinese paintings. For instance, they proposed to abandon the basic techniques of using painting brushes and ink, and to introduce Western painting techniques, like rendering light and shadow as well as perspective into Chinese paintings. The results are ugly, hellish objects, or organ-like lines and colors that look like a gang of starving wolves encircling lambs.

If acrylic paint is applied to canvas with the use of multi-point perspective or, if oil paints are applied to rice paper with an ink brush, the result will never be the same as authentic Chinese paintings. Without the concepts of Chinese paintings, Western masters will not successfully create genuine Chinese paintings even with Chinese painting tools. For example, Giuseppe Castiglione, a missionary who lived in China for over 40 years since 1715, painted in a style that was a fusion of European and Chinese traditions. Of all his numerous works, pure aesthetic beauty of Chinese paintings is missing.

In the past two or three decades, Chinese traditional culture has been doubted. Even native Chinese also doubt or oppose their ancestral culture that Westerners worship. For instance, failure or victory of martial arts are used to examine the value and truth of taiji, the medical inspection criteria of certain U.S.-based institutions, is employed to inspect the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine, depicted objects, and artistic value of Chinese paintings assessed on the theories of Western paintings. More phenomena like these are having an impact on the essence of Chinese culture. Of course, traditional culture involves both essence and dregs. Without a doubt falsity and deception still existed in the name of traditional culture. These disturbances also cause havoc for traditional culture. Yet wise people can distinguish between true and false and discern the essence from all the disturbing phenomena.

As for the accuracy of depicted objects in Chinese paintings, many have their own understanding. Any kind of art relies on an object’s form to express subjective intent. Lifelike depiction is the basic element of all paintings and also the first step toward professionalism, and Chinese paintings are no exception. However, Chinese people give lifelike depiction another interpretation. Numerous masterpieces are housed in Taipei’s National Palace Museum. Of them, Autumn Colors on Qiao and Hua Hills by Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) as shown in Photo I, a Chinese painter during the Yuan Dynasty, is a rarity. On the left of the painting is the cone-shaped Qiao Hill, located on the northern shore of the Yellow River in Jinan City, Shandong Province. On the right is the pointed Hua Hill, located on the southern shore of the Yellow River.

There is a considerable distance between the two hills. However, in 1295 Zhao Mengfu painted the two hills on a scroll measuring 28.4cm by 90.2cm, adopting a certain approach to make them look close to each other. This kind of image is neither created out of imagination nor due to the painter’s failure to draw lifelike objects. Viewers will neither doubt the accuracy of objects or geographic locations depicted, nor will they doubt artistic values of the painting. The rivers and hills are unlikely to be found in reality. Such a kind of artistic approach is commonly adopted in Chinese paintings including figure paintings.

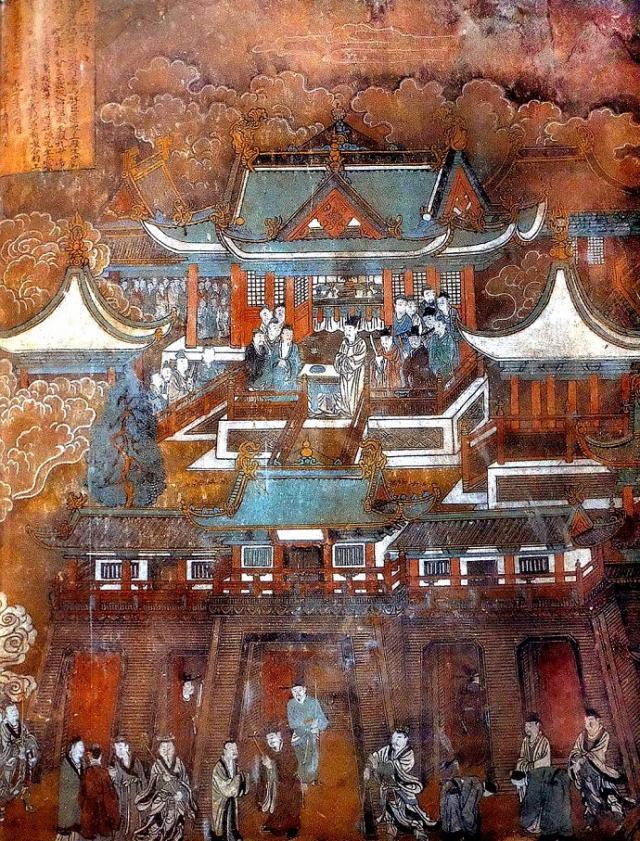

Consider the murals in the Chunyang Hall of Yongle Palace, located in Ruicheng County, Shanxi Province, as an example. Painters in Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) illustrated important events in the lifetime of the immortal Lü Dongbin in one mural, with the figure of Lü Dongbin repeatedly painted in the same mural. Besides, the painted figures are not based on the proportion of Asian people: A standing figure exhibits the 1:7 (head:body) ratio, sitting figure is 1:5 proportion, and crouching figure 1:3.5. In reality, a human head’s height would fit about seven times into the man’s height. If judged based on the Western perspective, the painted figures are out of proportion.

Actually, the core of Chinese paintings is in the use of multi-point perspective. Since Xu Beihong (1895-1953), Wang Shikuo (1911-1973), Jiang Zhaohe (1904-1986), and other painters who studied abroad had consistently tried to apply Western rendering of light and shadow as well as perspective to Chinese paintings and thus created many works. Yet their works were not very convincing.

Likewise, if Chinese herbs were sterilized before being cooked, the effectiveness of herbal medicine would be affected. If a green turnip were added to Chinese medicine as an efficacy-enhancing ingredient in the place of a carrot rich in vitamins, the effectiveness of the Chinese medicine would be reversed. If Baroque vocal music were added to Chinese Kunqu Opera, residents in Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province would not consider it Kunqu Opera.

Part 1 : https://www.themiddleland.com/art/2019/03/18/3303-artistic-forms-and-conceptions-part-i

Author: Cao Zuimeng

Translator: Amy Hsu

Cancel anytime

Using our website

You may use the The Middle Land website subject to the Terms and Conditions set out on this page. Visit this page regularly to check the latest Terms and Conditions. Access and use of this site constitutes your acceptance of the Terms and Conditions in-force at the time of use.

Intellectual property

Names, images and logos displayed on this site that identify The Middle Land are the intellectual property of New San Cai Inc. Copying any of this material is not permitted without prior written approval from the owner of the relevant intellectual property rights.

Requests for such approval should be directed to the competition committee.

Please provide details of your intended use of the relevant material and include your contact details including name, address, telephone number, fax number and email.

Linking policy

You do not have to ask permission to link directly to pages hosted on this website. However, we do not permit our pages to be loaded directly into frames on your website. Our pages must load into the user’s entire window.

The Middle Land is not responsible for the contents or reliability of any site to which it is hyperlinked and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Linking to or from this site should not be taken as endorsement of any kind. We cannot guarantee that these links will work all the time and have no control over the availability of the linked pages.

Submissions

All information, data, text, graphics or any other materials whatsoever uploaded or transmitted by you is your sole responsibility. This means that you are entirely responsible for all content you upload, post, email or otherwise transmit to the The Middle Land website.

Virus protection

We make every effort to check and test material at all stages of production. It is always recommended to run an anti-virus program on all material downloaded from the Internet. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss, disruption or damage to your data or computer system, which may occur while using material derived from this website.

Disclaimer

The website is provided ‘as is’, without any representation or endorsement made, and without warranty of any kind whether express or implied.

Your use of any information or materials on this website is entirely at your own risk, for which we shall not be liable. It is your responsibility to ensure any products, services or information available through this website meet your specific requirements.

We do not warrant the operation of this site will be uninterrupted or error free, that defects will be corrected, or that this site or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or represent the full functionality, accuracy and reliability of the materials. In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including, without limitation, loss of profits, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damages whatsoever arising from the use, or loss of data, arising out of – or in connection with – the use of this website.

Last Updated: September 11, 2024

New San Cai Inc. (hereinafter “The Middle Land,” “we,” “us,” or “our”) owns and operates www.themiddleland.com, its affiliated websites and applications (our “Sites”), and provides related products, services, newsletters, and other offerings (together with the Sites, our “Services”) to art lovers and visitors around the world.

This Privacy Policy (the “Policy”) is intended to provide you with information on how we collect, use, and share your personal data. We process personal data from visitors of our Sites, users of our Services, readers or bloggers (collectively, “you” or “your”). Personal data is any information about you. This Policy also describes your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your personal information.

If after reading this Policy you have additional questions or would like further information, please email at middleland@protonmail.com.

PERSONAL DATA WE COLLECT AND HOW WE USE IT

We collect and process personal data only for lawful reasons, such as our legitimate business interests, your consent, or to fulfill our legal or contractual obligations.

Information You Provide to Us

Most of the information Join Talents collects is provided by you voluntarily while using our Services. We do not request highly sensitive data, such as health or medical information, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, etc. and we ask that you refrain from sending us any such information.

Here are the types of personal data that you voluntarily provide to us:

As a registered users or customers, you may ask us to review or retrieve emails sent to your business. We will access these emails to provide these services for you.

We use the personal data you provide to us for the following business purposes:

Information Obtained from Third-Party Sources

We collect and publish biographical and other information about users, which we use to promote the articles and our bloggers who use our sites. If you provide personal information about others, or if others give us your information, we will only use that information for the specific reason for which it was provided.

Information We Collect by Automated Means

Log Files

The site uses your IP address to help diagnose server problems, and to administer our website. We use your IP addresses to analyze trends and gather broad demographic information for aggregate use.

Every time you access our Site, some data is temporarily stored and processed in a log file, such as your IP addresses, the browser types, the operating systems, the recalled page, or the date and time of the recall. This data is only evaluated for statistical purposes, such as to help us diagnose problems with our servers, to administer our sites, or to improve our Services.

Do Not Track

Your browser or device may include “Do Not Track” functionality. Our information collection and disclosure practices, and the choices that we provide to customers, will continue to operate as described in this Privacy Policy, whether or not a “Do Not Track” signal is received.

HOW WE SHARE YOUR INFORMATION

We may share your personal data with third parties only in the ways that are described in this Privacy Policy. We do not sell, rent, or lease your personal data to third parties, and We does not transfer your personal data to third parties for their direct marketing purposes.

We may share your personal data with third parties as follows:

There may be other instances where we share your personal data with third parties based on your consent.

HOW WE STORE AND SECURE YOUR INFORMATION

We retain your information for as long as your account is active or as needed to provide you Services. If you wish to cancel your account, please contact us middleland@protonmail.com. We will retain and use your personal data as necessary to comply with legal obligations, resolve disputes, and enforce our agreements.

All you and our data are stored in the server in the United States, we do not sales or transfer your personal data to the third party. All information you provide is stored on a secure server, and we generally accepted industry standards to protect the personal data we process both during transmission and once received.

YOUR RIGHTS/OPT OUT

You may correct, update, amend, delete/remove, or deactivate your account and personal data by making the change on your Blog on www.themiddleland.com or by emailing middleland@protonmail.com. We will respond to your request within a reasonable timeframe.

You may choose to stop receiving Join Talents newsletters or marketing emails at any time by following the unsubscribe instructions included in those communications, or you can email us at middleland@protonmail.com

LINKS TO OTHER WEBSITES

The Middle Land include links to other websites whose privacy practices may differ from that of ours. If you submit personal data to any of those sites, your information is governed by their privacy statements. We encourage you to carefully read the Privacy Policy of any website you visit.

NOTE TO PARENTS OR GUARDIANS

Our Services are not intended for use by children, and we do not knowingly or intentionally solicit data from or market to children under the age of 18. We reserve the right to delete the child’s information and the child’s registration on the Sites.

PRIVACY POLICY CHANGES

We may update this Privacy Policy to reflect changes to our personal data processing practices. If any material changes are made, we will notify you on the Sites prior to the change becoming effective. You are encouraged to periodically review this Policy.

HOW TO CONTACT US

If you have any questions about our Privacy Policy, please email middleland@protonmail.com

The Michelin brothers created the guide, which included information like maps, car mechanics listings, hotels and petrol stations across France to spur demand.

The guide began to award stars to fine dining restaurants in 1926.

At first, they offered just one star, the concept was expanded in 1931 to include one, two and three stars. One star establishments represent a “very good restaurant in its category”. Two honour “excellent cooking, worth a detour” and three reward “exceptional cuisine, worth a

Thank you for your participation,

please Log in or Sign up to Vote

123Sign in to your account