By Lillian Zheng, Ben Long

When Ben Long landed in Florence, Italy in August 1969, he found himself in a half-empty Renaissance town, where most locals had left for a traditional holiday to escape the sweltering heat, and he was mainly confronted by the sluggish ebb and flow of tourists. This voyage seemed to Ben Long, at the time, to be his final serious effort to commit to his fate to be an artist and find a true Maestro.

Four years earlier, 20-year-old Ben Long, dressed in his “Sunday best,” showed up at the door of the famous American artist, Edward Hopper, in Washington Square New York City on a bright Sunday afternoon – after church and dinner time – in the high hopes of introducing himself. A lady in a bathrobe opened the door, her expression quickly transforming from pleasant curiosity to sheer anger at his greeting, and said to this awkward stranger, “How dare you come to the home of a famous artist unannounced!” He caught a glimpse of Edward Hopper, old, frail, lying on the couch behind the bathrobed lady before she slammed the door. That day, a lesson was indeed learned.

Raised surrounded by fine painting, Ben Long was nurtured with a deep love for the Fine Arts of the Old Masters, in which most instruction seemed to have nearly disappeared in the United States, and was certainly difficult to find for a boy from North Carolina. In the last year of University, he discovered that good training could still be found at the Art Students League, the same art institution his grandfather, a very fine artist, had attended in 1911. Long went to The League and studied Anatomy and Drawing with the great teacher, Robert Beverly Hale, and studied painting with his first Maestro, Frank Mason. That time, a bit over a year, was a blessing for him.

And then the Vietnam War muscled into his life.

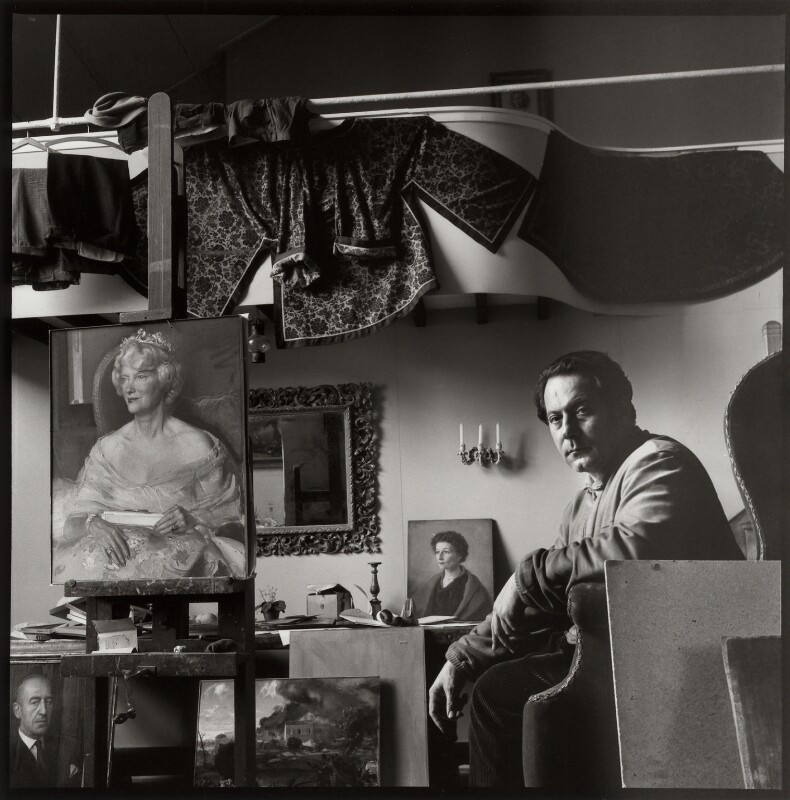

The choice was to be drafted into the Army or enlist himself. The Marine Corps had a combat art program that offered the possibility for Long to continue to follow his passion; so he became a Marine. He stayed in Vietnam for two and a half years as an infantry officer, and finally during the last six months, he served as a combat artist. With this last extension to remain in war, he was allowed a thirty-day leave. Long chose to go to Florence, Italy to seek out Maestro Pietro Annigoni, the world-famous artist, who had painted the Iconic Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, an image displayed in every English embassy and consulate.

Ben Long had until the end of August 1969 to find and be properly announced to Maestro Pietro Annigoni. Exploring Florence, he found a sympathetic gallery owner who knew Annigoni and set up an appointment for Long just two days before he had to depart.

He met the Maestro, who asked to see the drawings done during the war, then said, although he no longer took on students, he would be willing to help him when he got out of the Marines. The Maestro said a warm good-bye and, with a twinkle, recommended that he should be careful and stay alive. The Maestro’s opened a door for Ben Long, and his life was forever changed.

Maestro Pietro Annigoni had a passionate, deep belief in the beauty of masterly drawing and painting, certainly more classical than academic, and definitely not of the open rebellion of 20th Century modernism. Surrounded by the great art of the Italian Renaissance, Maestro Annigoni had the powerful spiritual influences that inspired his own prodigious drive and great success. Maestro Annigoni was an artist, Ben Long felt, who had the wise gifts that might reveal a true direction into Fine Art. On the 1st of April, 1970 he began drawing Anatomical casts in Annigoni’s studio attic.

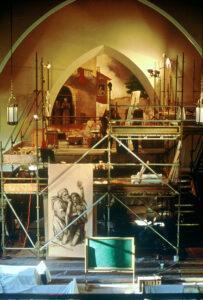

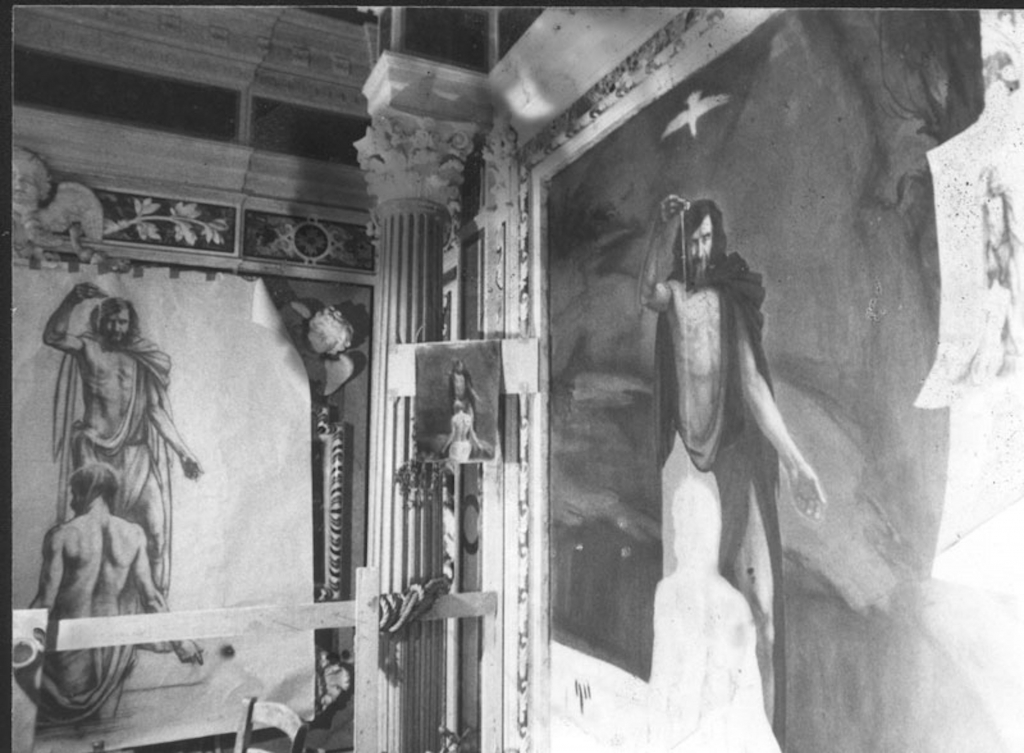

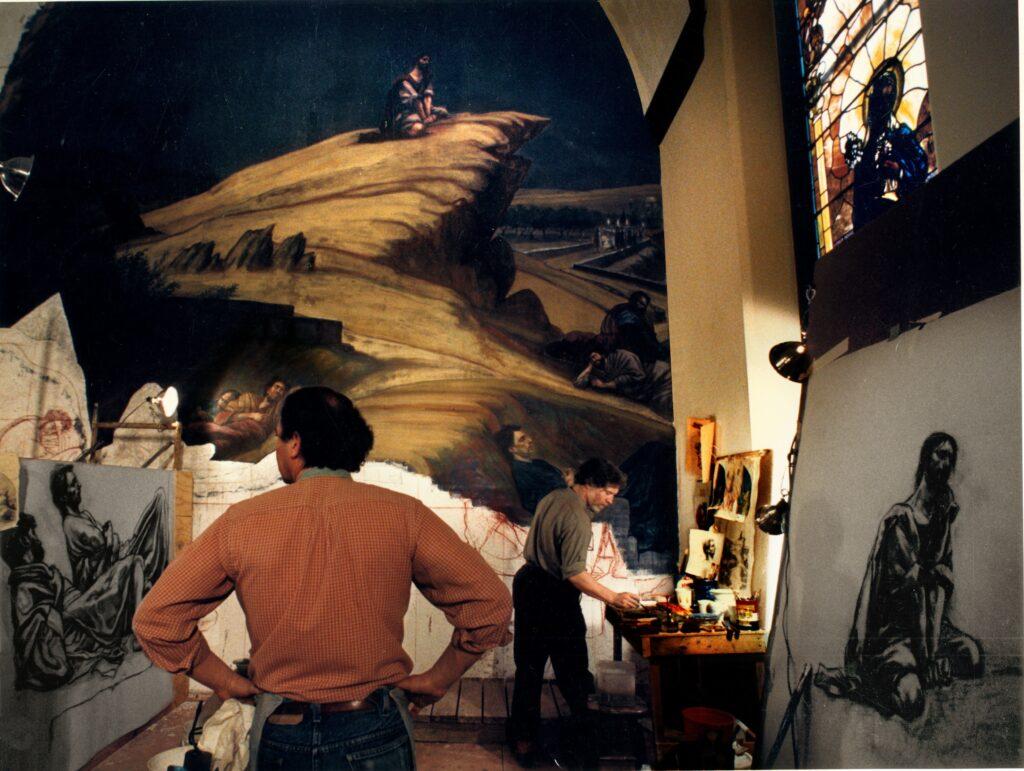

After a year of intensive drawing and the study of studio methods and materials, with much self-instruction into the craft of painting, Ben Long became fully involved in the art of fresco, working closely with the Maestro, who began a decade of steady large fresco commissions in Italy and the U.S. He became for the next seven years, “garzone”, or apprentice, along with Nando Bernardini, and later, Ugo Ugolini, the main Italian assistants. When the frescos were being made it was full-time daily work, for months at a time on each project. With this grueling schedule, one learned the subtleties of the craft.

On normal studio days, when the Maestro worked on other things, the schedule was 8:30 am to 1:00 pm six days per week. The afternoons were for the Maestro to work alone, and for Ben Long to do his own art in his studio, focusing on mainly learning to paint in oils. On Sundays, the Maestro would go out for the day and do oil landscape sketches, and Ben Long would happily go join the Maestro, to paint and closely watch his teacher. This was the true instruction, as in the studio, or at the fresco wall; to watch this great artists’ skill, his spirit, his attitude, his sincerity, fully embracing the mysterious meaning of being an artist.

One afternoon in 1978, two Italian monks knocked on Ben Long’s studio door. They were from the Abbey of Monte Cassino, founded in the early 6th Century by Saint Benedict. The Abbey had been bombed and left in rubble during World War II. Now it was completely and amazingly restored, except for the lost frescos. The monks asked him if he would consider a fresco commission to paint three walls in one of the chapels of the Basilica. Long of course, asked if they had first inquired after Maestro Annigoni. The monks said they were sent by the Masestro, who would in fact, do a large fresco later for the Abbey. So Long, accepted, sight unseen, no questions asked, and shortly after the visit, traveled down to Monte Cassino, to meet the Abbot, one of the twelve surviving monks of the WWII bombing, and to understand what would be expected in respect of their ways and the fresco needs. They were delighted that being an Episcopalian, Ben Long believed in Christ, and although not a Catholic, he was a step closer to being accepted by the monks. They left full creative control to the artist, who selected the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist, a sympathetic subject to all concerned.

Utilizing the skills and knowledge gained through his invaluable apprenticeship, Ben Long established his own creative process to produce some significant frescos in the world-famous Abbey that signaled a remarkable conclusion to his studies with his great Maestro, with whom a strong bond was forever formed.

The Maestro’s strong dictum: “If one can draw then why not draw all the time?”, is Love, in the flow of art. This always made clear sense to Ben Long, not as another person’s idea, but a nearly unspoken deep belief in both art and life.

For Ben Long, drawing is the forging engine of art, that leads to many methods of creativity. Long also believes that even if an artist is well trained, the artist must patiently and tenaciously trudge along in search to recapture, through the myriad diversions of art, that simple powerful moment of awe and wonder, that open his or her heart. To find that grace gives one the freedom of great art, beyond ambition, ego, or reward. To become a true artist, beyond all the hard work in a sacred and profound gift.

Cancel anytime

Using our website

You may use the The Middle Land website subject to the Terms and Conditions set out on this page. Visit this page regularly to check the latest Terms and Conditions. Access and use of this site constitutes your acceptance of the Terms and Conditions in-force at the time of use.

Intellectual property

Names, images and logos displayed on this site that identify The Middle Land are the intellectual property of New San Cai Inc. Copying any of this material is not permitted without prior written approval from the owner of the relevant intellectual property rights.

Requests for such approval should be directed to the competition committee.

Please provide details of your intended use of the relevant material and include your contact details including name, address, telephone number, fax number and email.

Linking policy

You do not have to ask permission to link directly to pages hosted on this website. However, we do not permit our pages to be loaded directly into frames on your website. Our pages must load into the user’s entire window.

The Middle Land is not responsible for the contents or reliability of any site to which it is hyperlinked and does not necessarily endorse the views expressed within them. Linking to or from this site should not be taken as endorsement of any kind. We cannot guarantee that these links will work all the time and have no control over the availability of the linked pages.

Submissions

All information, data, text, graphics or any other materials whatsoever uploaded or transmitted by you is your sole responsibility. This means that you are entirely responsible for all content you upload, post, email or otherwise transmit to the The Middle Land website.

Virus protection

We make every effort to check and test material at all stages of production. It is always recommended to run an anti-virus program on all material downloaded from the Internet. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss, disruption or damage to your data or computer system, which may occur while using material derived from this website.

Disclaimer

The website is provided ‘as is’, without any representation or endorsement made, and without warranty of any kind whether express or implied.

Your use of any information or materials on this website is entirely at your own risk, for which we shall not be liable. It is your responsibility to ensure any products, services or information available through this website meet your specific requirements.

We do not warrant the operation of this site will be uninterrupted or error free, that defects will be corrected, or that this site or the server that makes it available are free of viruses or represent the full functionality, accuracy and reliability of the materials. In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including, without limitation, loss of profits, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damages whatsoever arising from the use, or loss of data, arising out of – or in connection with – the use of this website.

Last Updated: September 11, 2024

New San Cai Inc. (hereinafter “The Middle Land,” “we,” “us,” or “our”) owns and operates www.themiddleland.com, its affiliated websites and applications (our “Sites”), and provides related products, services, newsletters, and other offerings (together with the Sites, our “Services”) to art lovers and visitors around the world.

This Privacy Policy (the “Policy”) is intended to provide you with information on how we collect, use, and share your personal data. We process personal data from visitors of our Sites, users of our Services, readers or bloggers (collectively, “you” or “your”). Personal data is any information about you. This Policy also describes your choices regarding use, access, and correction of your personal information.

If after reading this Policy you have additional questions or would like further information, please email at middleland@protonmail.com.

PERSONAL DATA WE COLLECT AND HOW WE USE IT

We collect and process personal data only for lawful reasons, such as our legitimate business interests, your consent, or to fulfill our legal or contractual obligations.

Information You Provide to Us

Most of the information Join Talents collects is provided by you voluntarily while using our Services. We do not request highly sensitive data, such as health or medical information, racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, etc. and we ask that you refrain from sending us any such information.

Here are the types of personal data that you voluntarily provide to us:

As a registered users or customers, you may ask us to review or retrieve emails sent to your business. We will access these emails to provide these services for you.

We use the personal data you provide to us for the following business purposes:

Information Obtained from Third-Party Sources

We collect and publish biographical and other information about users, which we use to promote the articles and our bloggers who use our sites. If you provide personal information about others, or if others give us your information, we will only use that information for the specific reason for which it was provided.

Information We Collect by Automated Means

Log Files

The site uses your IP address to help diagnose server problems, and to administer our website. We use your IP addresses to analyze trends and gather broad demographic information for aggregate use.

Every time you access our Site, some data is temporarily stored and processed in a log file, such as your IP addresses, the browser types, the operating systems, the recalled page, or the date and time of the recall. This data is only evaluated for statistical purposes, such as to help us diagnose problems with our servers, to administer our sites, or to improve our Services.

Do Not Track

Your browser or device may include “Do Not Track” functionality. Our information collection and disclosure practices, and the choices that we provide to customers, will continue to operate as described in this Privacy Policy, whether or not a “Do Not Track” signal is received.

HOW WE SHARE YOUR INFORMATION

We may share your personal data with third parties only in the ways that are described in this Privacy Policy. We do not sell, rent, or lease your personal data to third parties, and We does not transfer your personal data to third parties for their direct marketing purposes.

We may share your personal data with third parties as follows:

There may be other instances where we share your personal data with third parties based on your consent.

HOW WE STORE AND SECURE YOUR INFORMATION

We retain your information for as long as your account is active or as needed to provide you Services. If you wish to cancel your account, please contact us middleland@protonmail.com. We will retain and use your personal data as necessary to comply with legal obligations, resolve disputes, and enforce our agreements.

All you and our data are stored in the server in the United States, we do not sales or transfer your personal data to the third party. All information you provide is stored on a secure server, and we generally accepted industry standards to protect the personal data we process both during transmission and once received.

YOUR RIGHTS/OPT OUT

You may correct, update, amend, delete/remove, or deactivate your account and personal data by making the change on your Blog on www.themiddleland.com or by emailing middleland@protonmail.com. We will respond to your request within a reasonable timeframe.

You may choose to stop receiving Join Talents newsletters or marketing emails at any time by following the unsubscribe instructions included in those communications, or you can email us at middleland@protonmail.com

LINKS TO OTHER WEBSITES

The Middle Land include links to other websites whose privacy practices may differ from that of ours. If you submit personal data to any of those sites, your information is governed by their privacy statements. We encourage you to carefully read the Privacy Policy of any website you visit.

NOTE TO PARENTS OR GUARDIANS

Our Services are not intended for use by children, and we do not knowingly or intentionally solicit data from or market to children under the age of 18. We reserve the right to delete the child’s information and the child’s registration on the Sites.

PRIVACY POLICY CHANGES

We may update this Privacy Policy to reflect changes to our personal data processing practices. If any material changes are made, we will notify you on the Sites prior to the change becoming effective. You are encouraged to periodically review this Policy.

HOW TO CONTACT US

If you have any questions about our Privacy Policy, please email middleland@protonmail.com

The Michelin brothers created the guide, which included information like maps, car mechanics listings, hotels and petrol stations across France to spur demand.

The guide began to award stars to fine dining restaurants in 1926.

At first, they offered just one star, the concept was expanded in 1931 to include one, two and three stars. One star establishments represent a “very good restaurant in its category”. Two honour “excellent cooking, worth a detour” and three reward “exceptional cuisine, worth a

Thank you for your participation,

please Log in or Sign up to Vote

123Sign in to your account